Jesus in 404

Growing up in a secret nuclear city in the Gobi Desert

If the human race were to vanish from the face of the earth save for one halfway talented child that had received no education, this child would rediscover the entire course of evolution, it would be capable of producing everything once more, gods and demons, paradises, commandments, the Old and New Testament.

— Hermann Hesse, Demian

1.The Incubator and the Crystal Coffin

I was three and a half when my first cousin was born. My parents took me to the hospital. It was December. The Gobi Desert was dry and cold. We arrived late; the sky was a dark teal, cupped over the hospital like a bowl.

The hospital was a Soviet-style building. It had tall doors with glass panes and long metal handles. Inside, a wide staircase stretched upward. The floor was paved with large, patterned bricks; a heavy stomp would echo. The lobby ceiling was high, making anyone standing beneath it feel small. The smell of disinfectant made the air feel a few degrees colder.

In the delivery room, babies lay crying on a communal platform under small white quilts. They weren’t swaddled; their limbs flailed in the air. My cousin was not lying with them, nor did she have a small cotton quilt. She lay alone in an incubator.

The incubator had a transparent lid over a green base, lined with a cotton mat. My cousin was smaller than the others—half the size, perhaps. She was purplish, her eyes squeezed shut by wrinkled skin. Inside the case, a black fly crawled. She didn’t cry. A nurse in white stood by. My uncle looked at the incubator, looked away, then couldn’t help but look back.

The scene in my memory is silent. No crying babies, no buzzing fly. It’s as if a spotlight hit the incubator, drowning out everything else.

My cousin was a month premature, weighing just over four pounds. She survived. Years later, my uncle would say it was terrifying—her fingers were thinner than chopsticks.

Later, I saw a textbook photo of Chairman Mao lying in his crystal coffin. It reminded me of the incubator. In my memory, the green base of that machine bled into the rest of the image, making me believe the leader’s crystal coffin had a green bottom, too.

2.The Soldier in the Shell

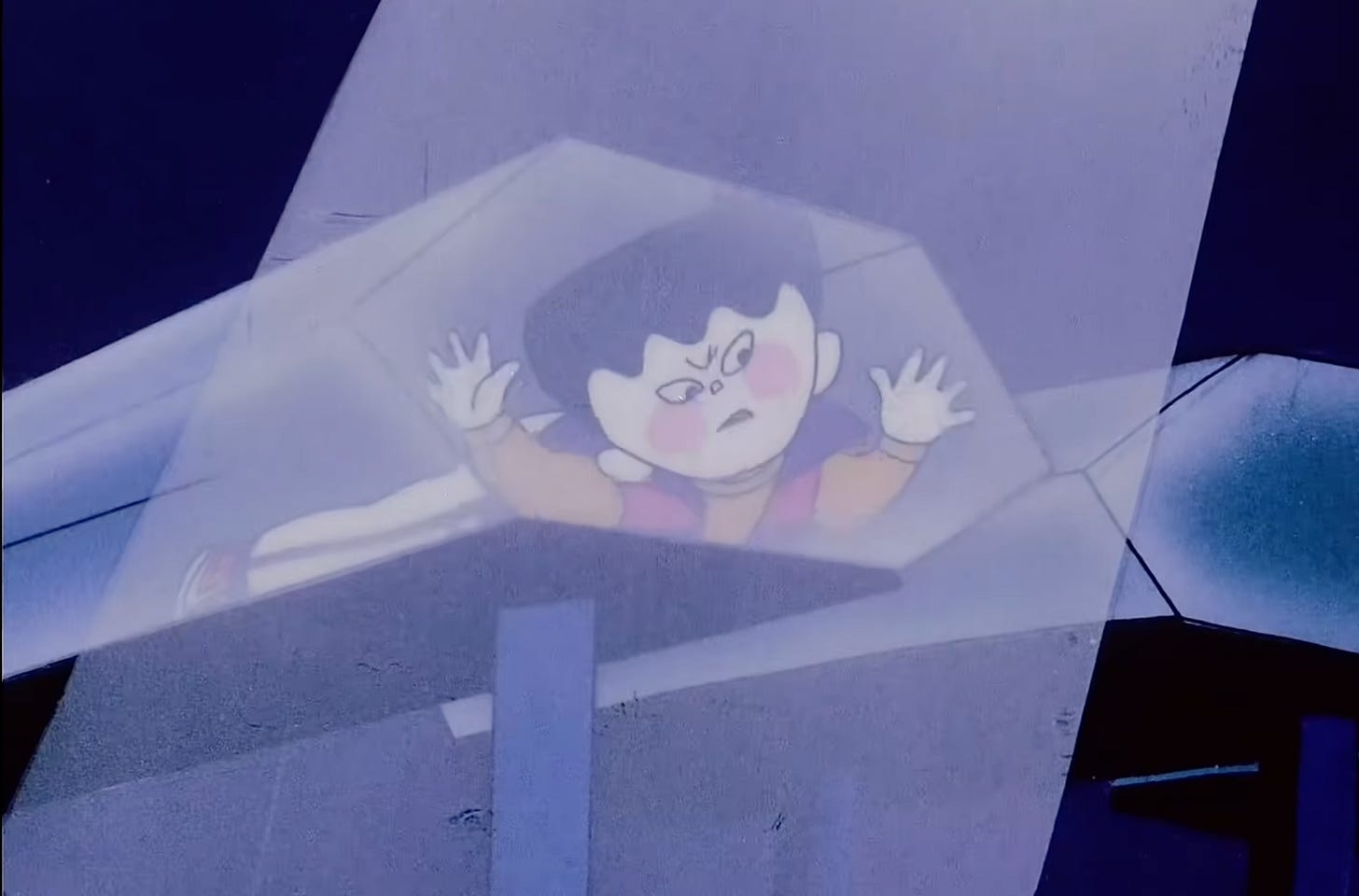

Around age three, I started having fantasies. I imagined I was a hero—infinite energy, yet extremely fragile. I spent most of my time sleeping inside a glowing eggshell to recover. A group of companions guarded me, each a different color (a trope from cartoons, I suppose). When the world was on the brink of destruction and my guards failed, I would emerge. Infinite light would flood out, and the world would be restored.

“World destruction” meant cracking earth and falling rocks. There were no villains. Most of the time, they didn’t even appear. After saving the world, I would be drained and hurt, reverting to a newborn state—like my cousin in the incubator. In the fantasy, I returned to the shell to heal. In reality, I wrapped myself tight in my quilt, smelling the cotton, and fell asleep.

This fantasy lasted three or four years. The monotonous plot repeated itself. It became my kindergarten daydream and my customary bedtime story.

My grandmother’s shop sold fifty-cent “blind bags.” They were likely foreign trash, repackaged for cheap sale. I often took things from the counter; my grandparents didn’t mind. Once, I took a bag containing a plastic egg. Inside were colored parts. I clenched them between my teeth to snap them together, building an American soldier in tactical gear, helmet, and gas mask.

It was my cheapest, shabbiest toy. His limbs and head wobbled. But he was the only toy I ever named: “Little Egg Man.” He became the protagonist of every story I invented.

Around six or seven, watching pretty girls dance on TV, I began to imagine them falling and getting hurt, so I could help them up. But that wasn’t enough. I wanted to be the one hurt, so they would pity me. Unlike martial arts novels, I didn’t crave their care or romance. I just wanted to suffer, and to be seen suffering. Sometimes, I would squeeze my legs together. The girl downstairs taught me this; she called it “holding pee” or “twisting the dough.” We didn’t know shame yet. Sometimes we did it in front of our parents.

Gradually, the fantasy shifted. I was injured, suspended high in the air, watched by girls I liked. There was no sex. Their sadness and tears were the whole point. After every fantasy, I sneezed—as if to compensate for the shame.

3.The Injured Bat

That same year, or maybe the next. A summer evening. I was playing outside with other kids. One girl was about two years older and much taller. She suggested a role-playing game. I jumped to the front. “My grandma’s house is just ahead,” I told them. “We can play at the gate. I’ll lead the way.” It was only twenty or thirty meters, but I seized every chance to perform. Children were ignored. Adults assumed we knew nothing. We just had to obey school rules and listen to our parents.

Grandma lived in the single-story housing area on the back hill. The family had built a room facing the street to open a small shop. They hung a wooden sign: “Prosperous Shop.” A double-stranded wire ran from the room, split at the end, and hooked onto a long nail. A warm light bulb dangled from it. That night, we played under the light. Small insects circled above our heads.

The girl said she wanted to be a bat. Before anyone else could speak, she spread her jacket, flapping it like wings. She spun on the small patch of brick pavement. Raising her hands high, she let out a long cry—”Ah”—then leaned to the side and fell. It was a slow, affected fall. Her body twisted into a Z-shape. Her legs were pinned to one side. One hand braced the ground; the other clutched her opposite shoulder. “Ah,” she said. “I’m hurt.”

My eyes widened. Goosebumps rose instantly on my back and arms. It felt as if my most secret fantasy had been pierced through, then displayed—clumsily and completely—for everyone to see.

I panicked and looked at the other kids. They stood there, oblivious. They saw nothing wrong. The girl claimed she was injured saving us, so we had to find herbs to cure her. The boys didn’t get it. They waved their fists, pouting and making “ch-ch-ping-ping” noises, pretending to be Transformers. The tall girl soon lost interest. The fake fall had been the climax. She had fulfilled her fantasy. The show was over.

Her behavior confused and unsettled me. Did she also enjoy being watched while injured? Why didn’t she feel shame? Why didn’t she sneeze? The clumsy scene under the lamp replayed in my mind. The drainage ditch, the bushes, the broken bricks, the peeling green door of the shop—I reconstructed the set over and over. The girl fell before me, again and again. As the replays multiplied, my perspective pulled back and rose higher. I seemed to be looking down on someone else’s life.

4.The Worship

I don’t know how missionaries got into 404, a secret nuclear city. When I was in first grade, Grandma brought home a thick Bible. Most women of her generation couldn’t read. I mocked her for carrying a book she couldn’t understand. She glanced at me. “Little brat,” she said.

404 was small. There wasn’t much to do. We went to Grandma’s three or four times a week. We usually didn’t call ahead. After dinner, we just walked over.

Grandma sat cross-legged on the bed. She told me God made man from mud, blew breath into the nostrils, and the man came alive. I laughed loudly, rolling around on the bed. I told her humans evolved from apes and she was superstitious. She asked why the monkeys in the zoo hadn’t turned into people after all these years. “They can’t anymore,” I said. “Only before.” I climbed off the bed, put on my shoes, and ran through the hallway to the main room, laughing. “Mom! Grandma says people are made of mud! Hahahaha!”

I was not yet seven, but I was a staunch materialist. I believed in neither ghosts nor gods. Most Chinese children born in the nineties were like me; we sentenced religion to death before we ever met it. The school held regular anti-cult campaigns. They took us to cinemas to watch propaganda films or to classrooms filled with blown-up photos. We lined up in our baggy uniforms to look at pictures of corpses, heads flattened by shovels. The captions said the victims’ families had joined a cult.After Falun Gong was branded a cult, we watched footage of their self-immolations in Tiananmen Square—the charred bodies.

After converting, Grandma listened to sermons on a tape recorder every night. On weekends, she went to worship and called her friends “sisters.” The recordings sounded monotonous and old, like they were made years ago. But childhood was long. My mind had few sentences or images to play with. Like the children’s books on the shelf, the tapes naturally attracted me.

When Grandma played the tapes, I grunted in fake protest, then sat nearby to listen. Sometimes she fell asleep and snored; I kept listening. The wall clock ticked. The cassette tape spun, emitting a faint, continuous white noise.

The tape said Jehovah preferred Abel’s offering, so Cain killed Abel in resentment. I thought Jehovah was at fault; he hadn’t treated them equally. The tape talked about the Trinity—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. I didn’t understand. How could a father split off a person to be his own son? What shocked me most was God telling Abraham to burn his only son as a sacrifice. The tape said God eventually replaced the boy with a lamb, concluding: “So people say, God has his own plan.” I didn’t understand how such a cruel figure could be God.

The easiest story to understand was Jesus being betrayed and nailed to the cross. Jesus was a perfect hero. He was powerful enough to cleanse all human sin, yet fragile enough to be easily destroyed—like the baby in the incubator.

The details of Jesus’ suffering were more specific than my bedtime fantasies. They were also more shameful. They made me want to squeeze my legs together.

That winter, Grandma said there was a church gathering at night and offered to take me. I thought superstitious gatherings were boring, but Mom told me to go have fun. Maybe she wanted to play ping pong, or maybe she just wanted a break from me.

404 had no church. That night, Grandma and I went to a bungalow on the back hill. It must have been someone’s home. A guide led us through a kitchen, a small living room, a courtyard, and a hallway. Behind a curtain made of paper beads, a woman holding a child watched us. We disturbed three or four people before finally entering a large, square room.

The room was crowded but not warm. A long table near the door held sunflower seeds and candy. Most of the people were women my grandmother’s age. One person sat in a wheelchair. I whispered to Grandma, asking why God hadn’t made him stand up. She slapped my hand.

Everyone sat on small stools cracking sunflower seeds. The floor was covered in shells. Later, they gathered around the stove to sing hymns. I stood between Grandma’s legs, clutching a piece of candy. Opposite us sat a man in his thirties. He held his son’s hand, rubbing his head affectionately against the boy’s, singing, “I am a child who believes in the Lord.” The boy was younger than me. He had heart stickers on his face and looked confused.

Thinking back, that day must have been Christmas.

5. The White Popsicle Cart

Grandma’s character didn’t change after she converted. Neither did her lifestyle. Perhaps she just knew a few more old ladies to greet. She ran the small shop. Every day at 5 PM, dressed in white clothes and a white hat, she pushed a small wooden cart lined with a cotton quilt to our elementary school gate to sell popsicles and snacks.

After school, a crowd of kids rushed out the gate like mad. Clutching small change, they squeezed against the cart, shouting, “Me first!” Some would steal snacks from the wooden box on the side during the chaos. Grandma leaned half her body over the cart, pressing down the lid, waiting for them to calm down before selling. I would stand nearby for a while. When it was crowded, she didn’t speak; she just grabbed a handful of snacks and stuffed them into my hand. When it was quiet, she lifted the quilt and let me take my time picking a popsicle. When Grandma gave me snacks, other kids always glared at me.

Another old lady copied Grandma and set up a cart across from her. But kids rarely went there. My family said it was because kids liked Grandma better. Grandma didn’t speak; she just looked at the ground.

I hadn’t finished elementary school when Grandma died. It was a sudden heart attack. The family didn’t know how serious it was, or that moving a heart attack patient is taboo. They supported her and moved her several times, even tossing her around to use the bathroom. By the time she reached the hospital, there was no hope.

My uncle sat by the bed, stroking Grandma’s face over and over. Mom was crying. My four- or five-year-old cousin was crying too. I felt I should cry, but I couldn’t. Back at Grandma’s house, while the family discussed the funeral, I tried to brew up some emotion, but still couldn’t cry. My father looked at my face and sneered.

I didn’t understand what happened. Grandma had chest pains before lunch. By afternoon, while the sky was still bright, she was gone. The Bible was so thick, yet it was useless.

The family followed the church rules and didn’t burn paper money for her. That seemed to be the only effect religion had on her.

A few years later, Grandpa dreamed that Grandma had no money to spend on the other side. The tradition of burning paper money at Qingming returned. The sermon tapes and the Bible were long gone.

6. The Trinity

Many years later, I vaguely guessed that lust and suffering are two sides of the same coin.

Jesus wore a crown of thorns. Blood clotted on his cheek and hair. Under the gaze of countless people, he was taken to the execution stand. The hammer drove iron nails into his palms, one by one. The viewers’ hearts were wrenched, again and again. Jesus knew this clearly, so he was happy.

Without an audience, Jesus’s suffering would lose its meaning. When God blew breath into the mud man’s nostrils, did he blow in a story? That the girl and I longed to place ourselves on a high stage, letting the gaze give meaning to the pain. This scene is so mesmerizing that God’s instrument of torture became the symbol of religion.

But real suffering has no stage. It happens quietly, plainly, like a white popsicle cart vanishing at the school gate.

I abandoned my childhood fantasy. I took myself down from the cross and stood in the watching crowd.

Now, 404 has been abandoned and repainted. I look through the transparent glass of the incubator at the wrinkled baby inside, eyes closed tight.

I gaze at him through the glass of memory. Long, and silent.

If this story resonated with you, you can support my writing here.